VILLAGER’s Art Ignites an Expansive Vision of African Identity

VILLAGER photographed in Baltimore, MD by Jamilah Scott.

NUNAR’s JAN 2024 Nu Era Issue print is now available.

Baltimore-based painter, sculptor, and co-founder of The Village Studio, VILLAGER, and NUNAR Editorial Director Jamilah Scott discuss spanning aspects of VILLAGER's artistic practice, delving into their personal journey from Nigeria to Baltimore, their coming-of-identity as VILLAGER, and the transformative power of cowries in their art.

The profound sit-down explores themes of queerness, identity, and the interconnectedness of the human experience, weaving together personal experiences with broader reflections on cultural and spiritual reclamation and the impact of ancestral practices.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

On Their Relationship With The Brush

VILLAGER: A brush was a… it was like, this is how I do a painting. You have to paint, right? Like, just the physical action and how if you're not an artist, you really just think, like, the brush is what does the work, you know? You may think you have to buy all these different brushes and all the best types of brushes. That thing when you're, you're trying something new? And you kind of feel like you have to have all the things? So, that's how I thought about brushes when I started painting. But, it was never able to manifest because I didn't have money.

So, starting off, like, brushes were just whatever I had. So, all the brushes that I have, I still have them, like, from the beginning. They're upstairs. But they're these cheap brushes in a blue little package. It was plastic, so it was like the cheapest thing. Then, a little bit after that it was last year. I mean earlier this year, in March or something, I wasn't painting at all. So a lot of my brushes were getting rusted in the water. Cause that's how I wash them. My brushes should have been rusted in the water. But I realized that whatever my brush looks like is a reflection of what my practice is.

So now that I'm in here like almost every day, my brushes are good. But on a conceptual level, a brush is just like my hand. It's just like my voice. It's like shoes. It's like socks, it's like the clothes you wear, that like, you're still yourself, and this thing is just, it's just a tool. So, right now I have a lot of liberty, I can do without this, but, I'm also using it, I'm using it in commanding its power, but in a way that I'm also allowing the brush to leave me, so. I have a lot of fun. I use it to create a lot of energizing moments where I'm actually just having fun and having a good time. So, yeah, that's where my relationship is with my brush now. I still don't have the best brushes. I don't, I don't know what the concept of the best brushes is at all. I just kind of use what I have and what I have.

Life & Becoming, in Nigeria

Jamilah: Were you doing art when you lived in Nigeria?

VILLAGER: No.

J: Really?

V: Yeah. Nah. I never did art when I was in Nigeria. I was in primary school, secondary school. Back then, like, growing up, I wanted to be, like, a pharmacist. Actually, no. Before a pharmacist, I wanted to be a scientist, a general scientist, a zoologist, because I loved animals. And then, yeah then I came to the U.S. and I wanted to be a pharmacist. And then I was studying like, and then I went to St. Mary's. And I had to transfer because they didn't offer the classes that I need to take for my pharmacy requirements, which is a blessing. Because I ended up transferring to Towson, which is what brought me to Baltimore.

I think what led me to painting, I would say the experience from Nigeria, like as a kid, I always wanted to, like, I always wanted to understand how everything worked. And I always wanted to find like my space in the world, I feel like that's something I've always been looking to find, it's like who am I, what am I here to do, but I never had the opportunity to express that. In the ways, in these ways now, but I expressed it through like, reading encyclopedias and just being just generally inquisitive about the world around me. And I think that, like, curiosity, like, is what translated to me having this art practice. Because, like, I'm constantly trying to find myself and everything. That same search of positioning in the world and being in the world. The same search of purpose. Which is really a conversation about, like, humanity, what it means to be human. Like, that search, I'm doing it now. I would say what led me to painting– or what led me to art– I always sketch here and there. Like there's some sketches here that are like way before I started painting, like so my first painting was like January 19, 2021, and I did this, oh 2022, I did this, I think that same day, there's like stuff from like, right in from like 2021. This is the day before I did that painting. But I've always been, oh, and these drawings also. I recently just posted and deleted it.

But I always like, I was always like, you know, you know when you did it on your notebook and stuff, but it's, you never think it's art, you know? You never think about, you never think about that. It's just, you're just exercising a part of your brain innately.

J: Right.

V: But, I was kind of doing that, and then, I was trying to learn how to sew, so I was sewing a little bit I bought a, I bought a block printing kit on Facebook Marketplace so I did that, but like, I never, I never took an art class until one evening, January 19th, I was depressed as hell, dude.

I was so fucking depressed. This is 2022, like last year. And this was also at a time where like, I was trying to figure out who I was, like, it was at its peak because I was coming to terms with like my own sexuality. I was coming to terms with like my, what is what, like, what is my purpose? You know, there isn't really any fucking purpose other than living, but how do I want to live?

Like, that's really the question. There is nothing such as purpose. I think those are words that like, when not used correctly, it just, it gets you distracted from living. But if you can use that word with the acknowledgment that just the only purpose is to live, we just have to figure out how we want to do that.

I was in grad school and I was working for like somebody that didn't care about me. And I was doing work that I didn't like. I also had just gone through a heartbreak also. So it was like my whole world was falling apart. My relationship, my family was not good.

Because like I was, this is a moment where I'm like, I'm like yo, I don't only like women, like I'm queer. And it was so much happening. This is probably the worst time of my life. So one day, I sat down. And I had a canvas in front of me. Before that, I made a pledge that I wanted to explore creative liberation in 2022. Because the year before that, I was just sewing, like I told you. So I sat down. And I had some, some of them, you know, dollar store brushes. The same brushes that I still use now. It's literally one of them. And then I painted for like six hours straight. It was an 11” by 14” canvas. And that, that painting was called Cage Vessel.

And some of these drawings, they are sort of connected to that because I was considering what it meant to be in a body. So like a vessel, moon, flow, stream, sink.

This is, this is my literal first painting. Like literal. You see, you see the date on the back. This is one I would never sell. But yeah. I was really just like, yo, I'm in my body. Like I felt like I just started living. I'm just understanding what it means to be autonomous.

MY NAME IS VILLAGER

V: My brain is now starting to kick into like, Well, my nigga, this life experience is yours, you know and it was a lot to process. It was really a lot to process, like to find myself outside of everything that I've ever been written to be, if that's, I mean, and that's also why I came up with the name villager because all my life I've been called so many different names.

My family called me Pelumi. That's not on my birth certificate. My birth certificate, it says Abdulrasheed. Growing up, when I went to school, they called me Kunle, which is my middle name. I would go home, my family would call me Pelumi. I would visit my dad in the summer for like two weeks or something. They would call me Rasheed.

So, like, so many different names. I came to America, they started calling me Abdul, because Abdulrasheed was too long. So, like, I just feel like I've never had the opposite. And you can see how that could be parallel to not being able to really be one thing or feeling like you haven't defined what you are yet.

Because name is powerful, you know, language is powerful. Language exists because we exist and it affirms our existence. So as I was trying to affirm my existence or trying to get there, I just realized that VILLAGER is what suited me. Because one thing that was important was the people around me at that moment. That was my saving grace.

J: You were a villager no matter where you went.

V: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. Exactly.

J: Exactly.

V: And I just realized, like, it really takes a village.

J: Right.

V: And, like, everyone is a human being. Like, there is so much that connects us all as people. And I feel like black people have always understood that. I feel like African people have always understood that. I feel like indigenous people have always understood that. Just like this interconnectedness of the human experience. And so. Coin villager and yeah. And I just kind of stuck through and now I'm just exploring other things also. Yeah.

On Spirit, Consciousness & Cowries

J: Yeah. So I know that when we were at when we were at [a mutual friend’s] party…

V: Oh, the conversation about God.

J: Yeah.

V: Oh my God,

J: The conversation about God we were having was really deep and interesting. And now I'm looking at the way that you use cowries, right?

V: Mm-Hmm,

J: Can you speak to what called you to use cowries in this way?

V: Damn, that's deep. That's a good question. So I would say, I would say to understand who you are right now, you always have to understand who you have been.

And that's just logic, you know? Like, nothing about this experience is new. Nothing about this human experience is new. Nothing in the world that's happening right now is new. Like, nothing. We just have to understand and, like, study the rhythm of life and then align ourselves to it.

So, I would say my connection to cowries is exactly like that. Like, being able to find the rhythms of life and then stick to it. And that rhythm is just a call, a calling back home. Like, I moved here in 2013 but I never really got a sense of what Nigeria was for me. Like, what Nigeria really is fully. In the way that I know it now. And you know, in Nigeria as a space for Nigerian people,

But also understanding all of the nuanced identities that exist as a Nigerian. You know, existing as a state, as an agent of the British imperial state, existing through colonial imagination but also Nigerian being an identity. That's really, really strong. And then coming to the United States, experiencing what it means to be a black person, and then also just realizing that, like, you're black everywhere.

And black is black is black is black is black. And there are a lot of like, you know, now movement outside of humanity. Now, there are a lot of things that bind us together as black people. I wouldn't just simply, this is the color of our skin, but our culture, our expression, the resilience that we have. You can say that for every other culture, whatever. But it's black, you know? I know this, this is what's native to me. And so, in trying to navigate this new, this new “where I am,” “who am I, now,” I'm now in a state where I've come back to prioritize my blackness. So this investigation of humanity is through an Afro Diasporic lens. And so part of that is understanding a little bit about African spirituality. Like, if you want to know who you are, there's people who have been figuring it out. You know, that's what practice is, not even religion. That's what practice is. And for me as a Yoruba person, there's a lot of viability there. There's a lot of content there that I was never exposed to because I was raised Christian.

J: Right! Oh! You did tell me that.

V: Yes, my mom's family's name is Ogunwemimo, which means "Ogun wash me clean". I was talking to my grandfather about it, he tried to explain around it. But like, he doesn't even have a connection to that name because his dad was a Muslim.

J: It's interesting how when you came to the States, you began to decolonize yourself.

V: Exactly, exactly.

But I feel like people on the continent are doing the same thing too. It's this together awakening. It's this like, we are this, you know. So, the way cowries came about is that, like, I'm trying to explore what these [African spiritual] practices are now for myself. And you know, trying to decolonize religion and like, I don't – I'm not religious.

J: Right.

V: The closest thing I would practice to religion is like, ancestral veneration. But then I also understand, living is a practice. And I'm not just living right now– What has come before me? So, yeah…When did I first do cowries?!

I started doing plaster molds of them. I don't know why! They just kind of called to me. I guess the short answer to all of this long theory that is all, of course. behind all the shit that I'm doing, is that they just kind of called to me. I don't even know how I started. But once I started, it was like I started seeing it in everything.

And [with] cowries being currency, they were used as currency, they were used as adornments. But like, I think about the idea of like, you know, people say money don't buy happiness, but money is a vessel for whatever you need to happen. Money will improve your material conditions and it's a vessel.

So I think of cowries not only because they were because they were currency, but because they're a literal vessel. You know, in African tradition, in Ifa, in Yoruba, this one's the most specific Yoruba traditional practice; Ifa is a binary knowledge system that kind of incorporates math with, like, AI

J: It's a science!

V: With, like, AI, with, like, NIGGAS!

J: *Laughs* Yeah!

V: You know what I'm saying?!?

J: OG's! Like!

V: Exactly, exactly. And, and Ifa practice is based on a binary system. So it's the front, or the back. And then there's a seed where, it's a chain of, I don't know how…I'm still trying to [articulate]...this is something that I’m, as a Nigerian, right, as a Yoruba person, I'm learning the theory, so then I can get closer to the practice… but then there's a question of like, what is the contemporary African? Is there even something [such] as a contemporary African? Because, Africans have always been contemporary people. Everything that niggas is doing now, black people have been doing it forever.

J: You're speaking to the African consciousness…

V: Yes.

J: The African personality.

V: Yes! But also the black personality. And like, you know, like, like I'm saying, being a Nigerian, being over here, I see traditional African American people, Back Americans here, they love cowries.

J: Oh yeah, I have so many cowries!

V: Right?! And this is like, you know. No matter the distance, no matter the conditions, we're still the same people. So, I kind of use them now as a vessel for just anything. Like, the vessels, the ones upstairs [in my house], the first time I did a big painting with cowries, I placed it in a landscape with a chair. The inspiration was from the Wamizi tribe in Tanzania. You know, they use it in coronations. So, I was trying to think about, what does it mean to be? And, what is the desire for my being? Like, words that start with B, E? Are so interesting to me. Like, Be-lieve, Be-cause, Be-fore, like—

J: Be-after! (laughs)

V: Right?! Be, right?! It's, it's so, they're so interesting to me. So, like, I put three big cowries there, boom. And those were more triangular. And then, I did another painting, “Gaze.” I put the cowrie underneath the head. And then I did another paint– Oh! Kandy's [Kehinde’s] painting. It started with, it's actually– The way I started cowries was, I did a painting for our 10 month anniversary… and I put 10 cowries under it!

Yes! That's how it started! That's how it started.

J: That is so good!!

V: Yes, now I'm getting back there. Because, all of this movement really started as an expression of love. I love myself, I love my culture, but then I love the people that I'm around. So, love. I did 10 cowries for our 10 month anniversary and then I gave it to them. And then right after that I did three works for three mothers. I was doing this style that I've like… it's like, I got that shit now. This style that I'm doing now?! I was starting with abstraction and I was [thinking], you know, cowries, cowries, cowries…. So those also featured cowries, the three of the three mothers, but cowries in the eyes. So slowly, slowly as I started getting deeper in this process, I got into portals. Cowries, as portals. Like, as literal… transport into different worlds. In your life, you're living so many lifetimes in your life. I've been a scientist, I've been a rugby player, I've been someone who did photography, I've been the grandchild who people thought was my grandparent's child, I, like… I've lived so many lives, and I get to enter and experience, but then I'm also trying to make people understand that, living is a vessel for itself. Cowries are vessels for living. What does it mean to live? What does it mean to be here? As a black person, as an African person? What melodies do you need to create? What songs do you need to write? What joys do you need to reincarnate? What community do you need to foster? So like, cowries, they called to me!? I don't know why I did cowries for our 10th anniversary,

J: It made sense!

V: But it was such a genuine and pure investment. Being here, being in that space, and I had them, and I started doing cowrie molds…I don't know, I just love, I even have scarves, I have cyanotype scarves of cowries. I just, they're everywhere.

J: Yes.

V: They're everywhere. Like, our eyes are shaped like cowries, our mouths are shaped like cowries.

J: And, the fact that, how do I say this… it is so dynamic. Like, the potentiality of how to use the cowries through artistic expression.

V: Yo...

J: It's endless!

V: So much!

*laughter*

V: So much! Just this one thing.

J: Yeah.

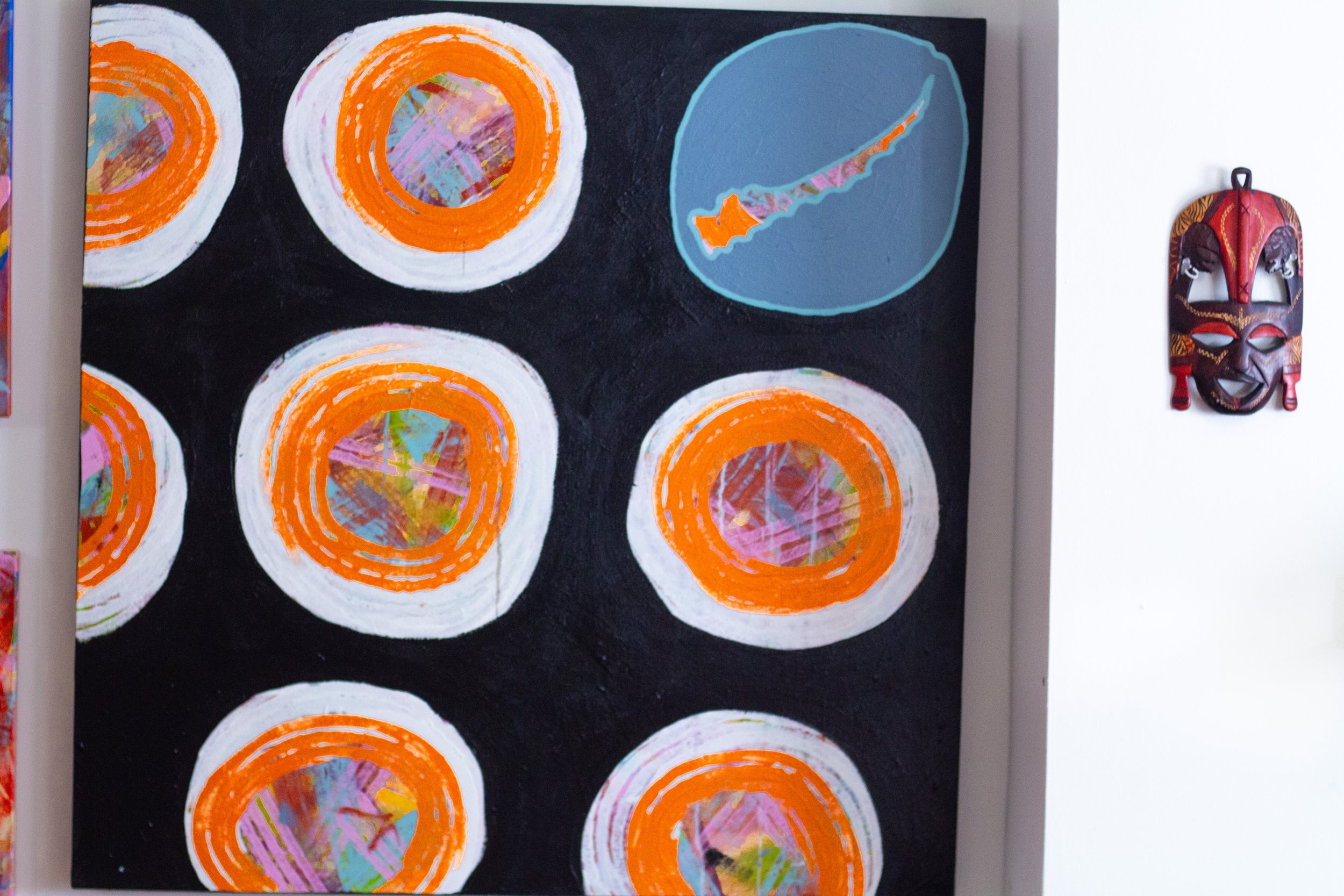

V: This one thing! And over here too. (gestures to painting) Over here in the eye. This particular painting is what led me to start doing cowries in the eye exactly like this. Exactly like this, which now, I'm doing it more. That is a cyanotype print, a transparency of a cyanotype print. So, my practice from cyanotype is what now influenced this more realistic [cowrie]. I have more abstract versions of cowries where it's just one block color. I have one where they're more realistic.

I have one where they're angular. I have one where they're in fabric. I have one where they're in front of these [things]. I have one where they're behind two people looking at each other and they're kind of rotating around them as some sort of, as some sort of energy field.

J: Mmmmm!

V: Yeah!

(laughter)

V: Yeah. I'm deep in it.

J: Yeah, wow.

V: Yeah. It's beautiful.

J: Extremely. I love this topic so much, so, sticking on it.

V: Yes, let's stay.

J: I'll try to get off of it real quick, but–

V: No! Let's stay. We'll chat, let's stay. Also, let me tell you, like, the concept about artist talks or like people asking me questions, I spend so much of my time trying to understand my own practice. Yeah. Like… I'm the most obsessive person about my work, but I'm also the student of my work. I'm the master and the student at the same time. I just have to get to the inside, the thing on the wall there (the portal.) But, I didn't get to that before. I got to that because I was doing abstractions. Like, all of this over here (referring to abstract paintings laying in the studio,) that's what was used to be under there. And then, I started using this tool (a spatula.) Cause it felt like I was adding more. And I did add more. And [then] I was like, okay– Let me start subtracting. Let me start subtracting. But it's really like, committing to the bit, right? Committing to the bit. And all of this, You know, I like to say, because like, I'm giving myself applause for this. All of this, I do not connect to anybody.

J: Yeah, you went flying. You truly did.

V: Yeah, you know, my third year? This third year, is where I can really, really, really say, “Babe, we going on a vacation.” “Yo, we bought a bus,” or a plane to do that shit. But like, being able to invest, in all the things I can love, like, [ A life where] I don't work at a restaurant anymore, I'm like, I'm like contributing to my sister, for her child, like, yo. Which is all the things I already knew, but it's like, it's just easy.

On Queer Identity Within Artistic Expression

J: When it comes to art, which is a physical thing, right, that's not a human being…how do you think queerness manifests itself?

V: When it comes to my art?

J: Yeah.

V: Or when it comes to art in general?

J: When it comes to your art, and also when it comes to art in general.

V: Right.

J: But your art specifically.

V: Yeah, yeah. I would say [with] my art specifically when it comes to queerness in my work, I think it's reflective of my own relationship with it. Not only as a subject but as an emphasis of my being. So I guess I really have to go back to the place of trying to translate what it means to be a queer person for me. What are my attitudes towards my own sexuality? How do I view gender expression and what is my experience with gender roles? And, the societal hierarchy that's interwoven with gender and sexuality and privilege, and how those play together… As a queer person, I see my own queerness and my gender expression as trying to redefine what it means to be this. Not really saying I'm doing anything new, but no one else in this world is going to be like me. I think I'm really coming from a place of just, what does it mean to be masculine? What does it mean to be feminine? What does it mean to be free? What does your sexuality mean? What does your attraction mean? I'm trying to define all of those outside of the societal normative context that enforces these same things that I'm trying to challenge or deconstruct. So for example, I'll show you a manifestation of that a little bit.

This is called “The Men In The Suits.” And, it was really this inspiration on masculinity. Cause I feel like I've had a chance, to really, really express my femininity in spaces where I feel safe. But, masculinity is something that I've always been expressing, because that's what I've been socialized to, to be a man.

Trying to go back and be like, “Well, what is a man?” and try to understand that I don't really fit in that description, or like, I don't want to be this egotistical figure whose ideals are rooted in the patriarchy.

But I also don't want to adhere my own self to those limitations.

I don't want to be that rigid, I don't want to be that figure that comes in a room and just, It's just like, it's just that, like, I don't want to be that. I want to be this. I want to be this mix between that pink and that blue and I want to live. I want to experience what it is to live, without anyone telling me what it is to live.

Yeah, I want to feel my own heartbeat.

J: Yeah, I feel like a lot of times when we talk about toxic masculinity, or even decolonizing masculinity, even within those paradigms, there's still, because of the world we live in, mental limitations on perception of man, even when we acknowledge those things.

V: It was a conversation around performance.

J: Right, exactly. I feel like queerness definitely opens [that paradigm.]

V: Yeah, it's like letting go of that mask and just being like, well, we're all performing, right? But then what do we want to perform? How is this love healing the world? And that's what niggas just wanna do, is just love, right?

J: Yeah.

V: So this painting is like a “Superman” and just trying to move away from, trying to explore what masculinity means for me. I will say, material-wise in my work, you can look everywhere and you see pink. You really have to study my work to see the way that I use [pink.] Even this painting that I just did, pink. Upstairs, the one on the wall, there's pink in there. The one next to it, there's pink in there, the one next to it, there's pink in there.

J: There's a lot of pink. (laughs)

V: This one? Right here, there's pink in there. Right here, there's pink in there, right here. My mirror? It's pink. (laughs)

So like, yeah. But growing up I always liked this– And it's so crazy, right, 'cause I always would say my favorite color was a spectrum from pink to burgundy. And that's just like, well, I'm neither this or this. I'm just kind of in the middle and existing.

J: That makes me think of blood for some reason, also. Like, the burgundy…

V: For me, pink is the most masculine color.

J: Really?

V: Pink is actually the most masculine color.

J: Why?

V: Because we have to define what it is to be masculine. Like, I know that I've been socialized to be masculine and it’s, like, non expressive. And I find myself, like, as a nonbinary person, I find myself where I'm just like, well, I'm a person, right? And I've been socialized to be this. But who do I want to be? And I feel like pink is that balance. For you to be yourself, so other people can be themselves. For you to just be vulnerable and be open and be real. Be there, and be proud that you are this, regardless of whatever this person– maybe they're your friend– whatever they think. Pink is masculine, it's feminine. And pink is open...I can't even fully stand behind like, yeah, “every color is everything.” But it's just, what constraints are you abiding yourself to? What constraints are you abiding yourself to and what freedoms are you granting to yourself?

Also, as I'm doing these new figures, these new genres of paintings, I'm combining my non-figurative exploration of my work through color and material and really deepening texture and trying to work with the materiality of the material itself – doing wet on wet applications, dry on wet applications… even the paints themselves, have different, like, sharpness to them and that's creating so much depth in my work. And then kind of carving it out. Just being able to translate that—that is the spirit of a person.

J: Mm-hmm! Wow.

V: I want to get into drawing queer couples, and guys and guys, and guys and girls. I'm starting to build blocks now where it's just only headshots. But. The moment I come down, or the moment I open up more space, because right now it's like… I have to work and perfect everything that I'm doing, and then expand it, because all of this is a system. I got here, and then I got to the portals, and then I stopped here, and then I went to the portals and I did the portals, and then, while I was doing that, I was also doing the African masks. And from the African masks, I said, let me be more realistic.

Now I want to show beauty. I want to show the beauty of people. I want to show people just existing. I want to invoke the spirit and the essence of their spirit. And allow people to see something called asè aesthetics. Allow people to see the asè in them. They are asè givers and they are potent with asè, just the power, the energy that is in the world is in them. So I want to get into like, depicting a lot of queer people also.

And, yeah!

J: Asè!

V: It's also interesting to see all the little things that I've always been like playing into a little bit. Like I did this last year, and that's a cowrie in the eye. And I didn't do that! Someone else put it in me. Like I did that? Yes, I did that. I didn't know I did that, though. And someone was pointing it out to me, I was like, whaaaaat? So, I've been doing this?! Yeah.

J: Spirit will always manifest itself through the vessel. You know.

V: Exactly.

J: Always.

V: Cowries through the vessel.

J: Those cowries!

V: Yeah.

J: But the idea of portals is so intriguing to me. Especially, like, knowing that each person has their own individual perception of the world.

V: Everything that's happening inside you is happening inside of somebody else!

J: Right!

V: That’s crazy!

J: It's like a collective consciousness, but then there's also the collective unconscious. And when we think about portals, especially like within art, you know, art is always up for interpretation, right? So, that's a portal within and of itself, but then you're thinking about the actual, actual concept of a portal within a cowrie, right? There’s…you can see the space through a cowrie, you know, you can… it's very, very, very interesting.

V: There's something awaiting you, behind there...

J: Right, and it's also quantum. Like when you're throwing cowries. You are changing your paradigm as you are throwing them, you know, as you're getting answers.

V: Yeah. Yeah. And that's the way Ifa comes in.

J: Yes.

V: They have studied all these 256 possibilities. And each one of those [outcomes] themselves also changing because the context is changing…

J: So then really it becomes infinite because there's infinite combinations of those possibilities.

V: Exactly. Right now I'm working on nine of the portals. Right now.

J: Nine is a good number, too. Nine is a very square, clean number.

V: Yeah, power of completion.

J: Yessss.

V: Trying to take the people on a journey.

J: Mm-hmm.

“Just Chatting…”

V: So, yeah. Processes, I would say, and I mean, I'm just kind of chatting now because, like I told you, I'd be asking myself questions in the shower and answering them. [It's] why do those videos– Oh, I should have a special guest today! I did a "One on One With VILLAGER", cause I constantly think about some of these questions and trying to understand myself— why am I doing this?

What were we just saying right now? We were saying something.

J: (laughs) I was, honestly I'm in a state of flow consciousness, I can't go backwards right now. But, you were saying you wanted to have a guest, a special guest maybe, but before that, I don't remember.

V: Oh, yeah, yeah. It was it was mostly about [how] I'm trying to understand this too. This is coming out of me, but I want to understand it. Like, I want to follow a lot of my work on these journeys.

J: Mm-hmm.

V: To find myself and then reflect that. I have this thing where, if anything happens to me, I have to portray it out. I have to think about [how] I feel like that is my constant reminder of [how] I'm a human and everybody's a human. I feel like that is where I find a lot of balance.

That is my best self. When I can experience something and immediately go, damn. I wonder how people are feeling this. I wonder if anyone's ever gone through this. And sometimes I may not bite, but just that question alone is what has been pushing me forward. Doing something and being able to say, okay, what if?

J: When you do that, when you express your lived-in experiences through your art, it's a collapsing of space-time, almost. You have the ability to do that. But then also I think about how, you know, the ancestors are manifesting through you. And how that also collapses space-time and puts it on the 3D plane. Or really the 2D, 3D plane with, you know, a canvas. But yeah. It's powerful. I feel like you're healing timelines and like bloodlines and... (laughs) yeah.

V: I'm trying! I'm healing my bloodline right now. Yeah, when I say I'm finding myself through this, I'm finding my identity that was... stolen! By these religions. Through my grandparents and his own parents and his own parents.

J: Mhm...(sucks teeth)

V: "Ogun Wemimo", you're Ogun worshippers.

J: Right.

V: And I never... like, my uncle, he's a pastor. He took that Ogun out of his name and now he goes by Wemimo, which just means "wash me clean."

J: Really?!

V: Yes!

J: Then you're washing away everything!

V: Exactly!!

J: Wow...

V: So in the word, in the word itself, you're actually practicing it, and then reinforcing it!

J: Yes, yes, wooow, woooowww....

V: And then like, you are in this loop of forgetting who you are. Right?

J: Yes. Wow.

V: So, yeah. I…it's a lot of work. It's a lot of work because of so many angles, just familial-wise, personal-wise, and then I'll go to more broader states. Personally, there is a lot of things that were lost. In my own family. A lot of practices.

J: Right, but it's still within the consciousness.

V: It's still within the consciousness. Sometimes I'll dream and I'll see back home.

J: Oh, I have another question. Okay.

V: Damn, I was going on that, because I wanted to go somewhere. I was going on that. Sorry.

J: It's okay! It'll come back. It'll come back.

V: No, I got it. I'm saying I want us to go somewhere.

J: Oh! Yeah! Continue.

V: Where I wanted to go is that like, family-wise, but then generally, you know, there is no homogenous African culture. Even as a Nigerian, my identity as a Nigerian, there is no Nigeria.

J: Right.

V: Nigeria is a business. All these countries were businesses! Like niggas really met –

J: Speak on it!

V: They said, yo, we are going to, we're gonna divide and cut this like this, and we're gonna sit for two months to agree, just so we don't fight over there so they don't think we're disorganized.

J: Mm-Hmm!

V: And that's what the fuck just happened.

J: Yep. Those borders are completely –

V: False!!

J: Arbitrary!!

J: Arbitrary! Irrelevant!! Yes.

V: Irrelevance. So then, in a way, that's a timeline disrupted there.

J: Mm-hmm. Mm hmm.

V: We're talking about timeline disruption now and place and time.

J: Yeah, and consequence.

V: My family was already there. And that's already a disruption there.

J: Now they have the idea of “Nigeria.”

V: Right. And then that identity now being commodified.

J: Mm-hmm.

V: All of these unique practices that were unique to these different, if not tribes, nations, and communities of people being exploited and exported and being stolen. So then if I wake up every day, and I bow my head to a brush and I take that brush away, in one generation. Your child would be bowing down and would not know why he's bowing down. And the next generation, maybe two people may be bowing down. And it's just like, it's just comfort. And the next generation, no one will be bowing down. The next generation, they will start outcasting people for bowing down. Because they're worshiping the brush. And now worshiping the brush is… [considered] demonic. And now in the next generation, you can't worship the brush, you have to bow down to a cup.

J: And if you worship the brush...

V: And if you worship the brush, you're still demonic, but then you'd be outright, you'd be outcast by your own people. And then in the next generation, everyone worships the cup because we've always been worshiping the cup.

J: Allegedly.

V: Allegedly.

(laughter)

V: So how many timelines did we disrupt in that? So all of that is [why] I have so much material that I have no choice than to be busy! Because I'm really trying to find out the ways the past is alive in the present because it is.

J: Absolutely.

V: So when I say I'm questioning the idea of contemporary African, there's nothing such as contemporary because the African is still alive today. Our practices are still alive today. Black people –

J: It's always here. Here, here.

V: Even here! No matter where we are!

J: Right, because we're always right here!

V: Exactly. Exactly. So all of that, like, spatiality and temporality… especially being in Baltimore. I'm definitely blessed to still be around black people. This is the sort of community that I grew up in. These are the people, like, I feel at home again. So, I was trying to find home while at home in the space that I made home... and trying to rediscover what my home truly is. And finding my home within myself, finding my home within the spirits of my ancestors. Finding my home in this moment. Yep.

J: Mm-hmm. Thank you for that. Yeah. That was beautiful. One thing I think about –

V: That was a good one.

J: That was a very good one. That was a very good one. When you think about what it means to be contemporary…Like, what is that?

V: (laughter) Right!

J: What does contemporary even mean?!

V: Right!

J: As Africans, we understand the animistic nature of all things. We understand that, right? But we are in a society that does not understand that. And it's very profound to be in a space where mentally, you're able to… It's like a dichotomy. This is so relevant to everything I've been researching [by the way.] Wow. But the dialectics of it, because we are in this Western society, and we are also in our African consciousness at the same time. And we are navigating our African consciousness... it's dualistic, because we're not within the Western society at the same time that we are physically within the Western society. Do you understand what I'm saying?

V: Yeah, I do, yeah, I do.

J: Absolutely, this is very interesting. Wow. Do you feel, I know that you do, but I just want you to expand on it I guess, but do you feel like your paintings are alive, do you feel like your paintings carry a consciousness of their own?

V: I mean, they have to, like they have to, and they do. This is one of them ones (questions) where I can go technical, or I can go spiritual. I'll spend a little bit of time on technical because I am imbuing them with a lot of material. Like, sure. Then I'm going to move past that to say, they do have a spirit. I think, for me, I'm trying to exist within the space of the mundane and the divine.

J: Because they're one.

V: Hm?

J: They're one.

V: Exactly. And I'm really trying to meld those things together and exist within the oneness of it. Because, you know, trying to ask the question, like, what is sacred? Outside of trying to obligate, like, totems of sacredness. How do you define what is sacred? And how do you define what is normal? Is this up to you? Especially right now, I want them to exist within that space.

So, even before I get to the end of any painting, I've probably done 10 paintings on one painting. Right now I'm kind of doing these for portraits and headshots. Cause I really wanna focus on above the shoulders right now. And then like I was saying, I'll move down. But above the shoulders is [where] you can really see into someone. You can really see into them. And feel them. And sort of imagine what sort of lives they've lived. Like, who are these people? But also feel their energy. You can feel people's energy by just experiencing them. In the work like this, I probably spend more time doing this [layering] than whatever the final image is. Because this is where the conversation starts, and that's why I'm trying to really, really understand what this work means. There's so many different colors under here, and I have to just go, and go, and go, and go, and go, and go, and go.

And I'm really deepening it. It's like that moment of creation, where they say God created Adam in his own image, or people in their own image. I was created in an image of something. I am a physical embodiment of my ancestors, but then now, how do I honor the past?

How do I honor them, but also reflect today? So all of that questioning, all of that process, that is life in itself. And then we'll be talking about asè aesthetics. I'm doing these works for a reason. What is the greater [purpose,] what do I want this to say? What power do I want this to hold? What intention do I want this to multiply?

Doing these, now going back to technical, there's so much movement – with the strokes, there's so much texture, that you can feel them, almost like you're alive. Even in the movements too, the movements, they're so alive because like I'm doing them like (does wooshing movements with brush in hand) And I'm really just like, I'm putting myself to a point of tension where, you know, they say pressure makes diamonds. And I'm really trying to squeeze out and imbue life force into this with my own life force. Energy is not created but transformed from one form to another. So on an energetic level, that's the second law of thermodynamics. On an energetic level, this is life. Because it's asè, it's the energy. I'm also interacting with string theory as well.

J: Mm-hmm,

V: If you're trying to find something, you look so close, so deep, you will see that what you were trying to find here was the whole thing itself.

J: Mmmm.

V: Now we go back to the portal. Where the cowrie on one of them is that entrance. And once you like, you see this, and you open your eyes a little bit. And then the mirror appears, and then you can see yourself. And then that's the portraiture.

Then if I go back to the mask. I mean, I imagine what they would look like. If they were here right now, what would those figurines, what would those masks – what would it look like if they were not taken out of the context of their original practices?

What sort of vibrancy would they hold? What sort of energy would they hold? And the best way I can do that really is through color. Really is through my painting, really is through color.

J: And color is light, also.

V: Yeah, color is light. And then, you know, we can talk about energy again. None of the colors that I use, do I actually go pick them out. I get oops paint from Home Depot.

J: l8aughs*

V: That's all the colors. So when people say, oh, you're good with colors, I'm just good at being present. I find out what my work is. It's that moment of creation. Like when God created, I'm that. I am that God in that moment. And I'm sculpting this. And then I say, boom, go. You know, also with my experience with Christianity as well. I'm very familiar with the idea of creation. So, I'm putting myself, I'm taking myself to that. I'm taking myself to that moment of creation and saying, “I am God,” I am creating myself, I am sculpting these in my image, in my thoughts, and I am kind of the footstool. I am the vessel. Now we're back again at vessels. So, yeah.

J: Thank you, Abdul. That's very inspiring...VILLAGER. I'm so used to calling you Abdul.

V: Yes, everybody calls me Abdul.

J: Is VILLAGER your preferred name?

V: Yeah, I introduce myself as VILLAGER. Hello, my name is VILLAGER. It's nice to meet you.

J: (laughs) It's nice to meet you too.