Ari Melenciano Reminds Us the Future Belongs to Us

Note: This article was published in our APR 2021 Issue on April 30, 2021.

“It was a project that took such an intense level of commitment and perseverance to make happen–I don’t think anyone really saw the vision when I first shared it,” says Ari Melenciano of the first annual Afrotectopia festival in 2018 hosted by NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP), her graduate program at the time.

During the festival’s final moments, Melenciano fought back her tears as Vy Higginsen’s Sing Harlem Choir performed the closing ceremony for the first iteration of the Afrotectopian vision she created. “I was fighting back tears listening to them and looking at everyone in the space. It was an unforgettable moment because I had spent so much of those two years of grad school angry and feeling like I’m fighting the world with how frustrated I was with how society operated racially, politically,” she told me. “[T]heir voices being the seal of an event that felt incredibly fulfilling all just made me feel like my heart was bursting [...] [s]o as the choir sang, and all those Black people smiled, in a space that took so much energy to create - it was incredible, almost too much.”

Cultivating creative spheres in tech, art, and pedagogy for Black enjoyment, futures, and power is one way you can describe this tech gal’s groundbreaking work. Still, Ari Melenciano is so much more. She’s not only the founder of Afrotectopia. She is a creative technologist at Google’s Creative Lab, a professor and researcher at NYU’s ITP, designer, artist, and writer. Her award-winning work has been uplifted by various renowned institutions, including Sundance, The New Museum's New Inc, The New York Times, Forbes, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and Apple. She is also often guest lecturing at universities around the world.

Afrotectopia is a social institution that, according to its website, is “imagining, researching, and building at the nexus of new media art, design, science, and technology through a Black and Afrocentric lens.” The institution is committed to creating radically-inclined spaces in the form of an annual festival, international fellowships, think tanks, alternative schools, and more to foster, in Melenciano’s words, “space for celebration of Afrocentric technoculture, Black radical imagination, and boundless curiosity.” The encouragement to establish this institution while in grad school came as a realization during her experience as an educator. “I spent a lot of time in a classroom as a substitute teacher, and a child of educators, and was very invested in making classroom environments an inspiring and celebratory space to learn–I knew it was easier to grasp information and learn new things when you were enjoying it.”

As a kid, Ari’s inclination towards technology started as an end-user relationship. It was a fascination with what new possibilities brought by emerging tech meant for artistic hobbies––like producing music in Garage Band, using iMovie to create short films, or even being taught HTML/CSS by her big sister to make “very basic” websites. She attended the University of Maryland to receive her bachelor’s where she also studied architecture and art history abroad at Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona. By this time, Ari meaningfully grasped the realms of art and tech as a nexus that can produce fantastic outcomes but “never saw it actually being done in the way [she] imagined it.” During a period of learning abroad, Ari was finally able to see the application of art and tech in a way she hadn’t before, witnessing “beautiful forms of projection mapping in different cities like Barcelona, Spain and Porto, Portugal,” which inspired her to seek more spaces where that work was done. Years later, Ari was spending her time as a graduate student at NYU’s ITP “being mind blown every day at how incredible the opportunities so seamlessly lied at the nexus of art and tech.”

Raised in PG County, Melenciano grew up in what she “later learned was a sort of Black utopia.” PG County stands as one of the nation’s wealthiest Black communities and remains a beacon of excellence and opportunity for Black Americans. It wasn’t until Melenciano left the DMV for NYU that she realized how unique her upbringing was. “I didn’t realize that level of Black abundance was abnormal,” she says. While intentional spaces in tech exist where Black radical imagination is furthered and protected, it contrasts to a white male-led tech industry and a larger world where the Black radical imagination is constantly oppressed by anti-blackness. Big Tech has played a role in attacking Black futures with not only a lack of diversity in the upper ranks, but even more concerning, the increasingly colonial efforts and aims in their pursuit for superior technologies in what has been deemed tech colonialism. “I absolutely share the concern…. The impact Big Tech can have on the livelihood of the vast majority of the world’s population often feels insurmountable. The harmful biases people hold have too easily been embedded into technologies without much of a checks and balances because the rate in which technology develops is much faster than law and policy,” Ari tells me.

Concerns about tech colonialism pretty much break down into five main concepts: (1) seeking treatment equal to sovereign nations (2) global reach and influence (3) acting ‘above the law,’ (4) imperialistic centralization of increasingly private information (5) and a direction towards an “invisible empire” due to the ‘platformless’ and interoperable approach of product development (i.e. Samsung and Microsoft partnership). The concern is that, soon, separate technology companies in their pursuit to offer a unified and tailored end-user experience––and acting on shared interests for sovereignty from state jurisdictions––are on course to create an ‘invisible Internet’ where the Internet experience transcends physical devices to become a worldwide intelligent space.

Melenciano: “There are a few important things people have to consider before often equating all of Big Tech with the worst of humanity…”

Imagine no more confined screens, finding and downloading apps, keyboards, search engines, but an intelligent space that provides a seamless, personalized user experience as soon as you walk into it. Anywhere on Earth, such a space made up of intelligent capabilities could be interacted with using human-friendly interfaces such as speech, gestures, eye movement, sense of touch, and, eventually, brain-to-Internet interfaces. The line between cyber, reality and tech companies would become exceedingly blurred.

This may sound desirable, but it also masks the imperialistic manner that this level of reach and centralization of highly personal data would require. It could also allow individual tech companies to virtually disappear into an omnipresent sovereignty. With our current anti-trust laws, this entity would be nearly impossible to detect and regulate. Furthermore, by exploiting the public’s––and, more importantly, the government’s––dependence on and lack of knowledge about the created technologies, Big Tech has a unique and increasing ability to operate covertly. It is a path to world domination, sort of speak, that mimics the European colonialism that still operates worldwide. Likewise, if we’ve learned anything from the richest, most destructive industry in history, Big Oil, this could have terrible consequences for democracies, civil and human rights, even the natural world.

On the other hand, Ari argues that we shouldn’t only expect the worst to happen. “There are a few important things people have to consider before often equating all of Big Tech with the worst of humanity––which I see happen frequently, and in ways, I’m also concerned about,” she tells me. “[I]t’s not so binary. Big tech has realized some of the most positively impactful achievements the world could have never imagined––that get taken for granted as more and more generations are born digital natives and feel reasonably anxious towards technology [...] At work, I’m on a team that’s exploring the immense potential of machine learning on super cheap and small microcontrollers––and exploring how that can provide very powerful technology to communities that usually can’t afford it, whether it’s for education, agriculture, or creative expression.”

Ari also summons the history of how people used radios to learn during the polio epidemic in the 40s and 50s and likens it to how we use Zoom to teach and learn during the ongoing pandemic. Additionally, access to information, social interaction, and activism have been revolutionized thanks to tech. “All to say, it’s a big mix of some of the most negatively and positively impactful outputs coming out of the tech world. I’m not speaking for all of Big Tech because I recognize many companies and teams out there are very harmful to humanity through exploitation, privacy intrusion, [etcetera]. But I know from my experience in Big Tech, I’m currently working with people that are also constantly questioning and operating with care and intent as we explore ways to directly invest in the advancement of marginalized communities with an endless list of initiatives and projects continuously being added to. It’s highly nuanced.”

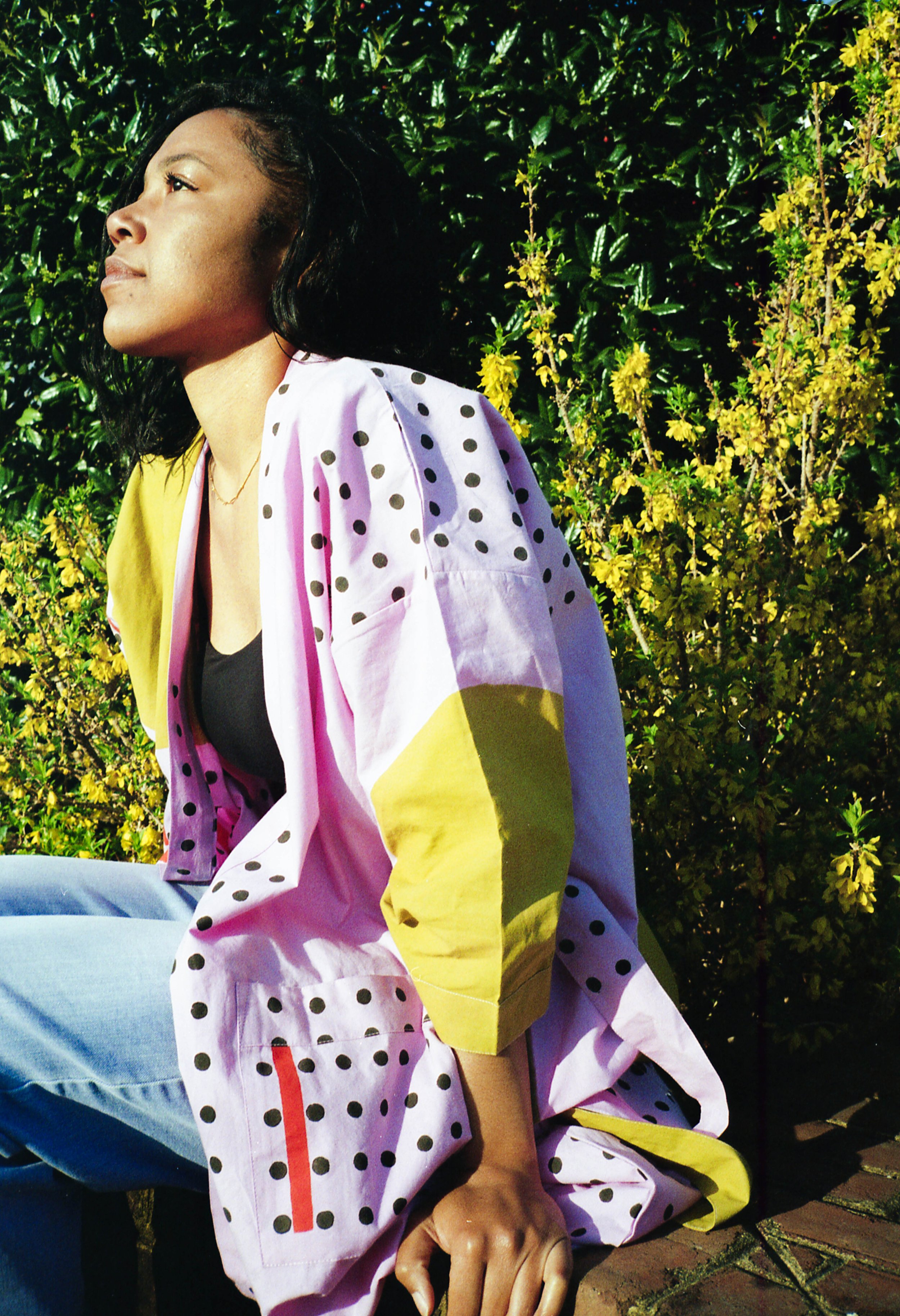

Portraits by Jasmine McGill.

Currently, white men lead the technology industry and make up the majority of the upper ranks. The culture of the tech world centers on U.S.-based companies in Silicon Valley. I asked Melenciano if she ever sees that changing. “I do. Definitely not as fast as I’d like, but there are a lot of us Black technologists out here - and many more on their way.” For any women of color venturing into tech, Ari has this message: “You belong and are deserving. For people that often have the door closed before they can even begin imagining that door being there in the first place, it’s easy to convince yourself that the opportunity isn’t for you, that you don’t deserve it or are not qualified for it.” To her point, while women and BIPOC make up a majority of users for companies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter, these groups are rarely envisioned as top performers and often are blocked from working at tech companies or face abuse if they do. Even so, Ari encourages self-confidence and having audacity. “We’re [Black women] taught to be so humble and small - but that won’t open doors for you. I did that for so long and wondered why no one else could see my worth the way I could. Humility is always important but so is recognizing your self-worth and all that you have to offer. When you enter a scenario and recognize it's not just you that will benefit from them, but them that will benefit from you, too - it’s a whole paradigm shift that often changes the game.”

As for Black futures, Ari Melenciano sees reason to believe in a future shaped by the Black radical imagination. “There are always futures possible that are shaped by Black radical imagination. That’s so much of what Afrotectopia is about. Step one is not waiting for permission, or someone to hand you an opportunity but for you to go out and create that opportunity for your community and for yourself. We get there by building communities, sharing opportunities, and supporting one another. Technology is merely a reflection of the society in which it is birthed out of so another step would be to not operate in a tech-determinism manner but realize the ‘feedback loop’ is actually the opposite; systems don’t just occur as it's actually how we interpret and build these systems - design designs us. Tech won’t save us, we have to save ourselves first.”